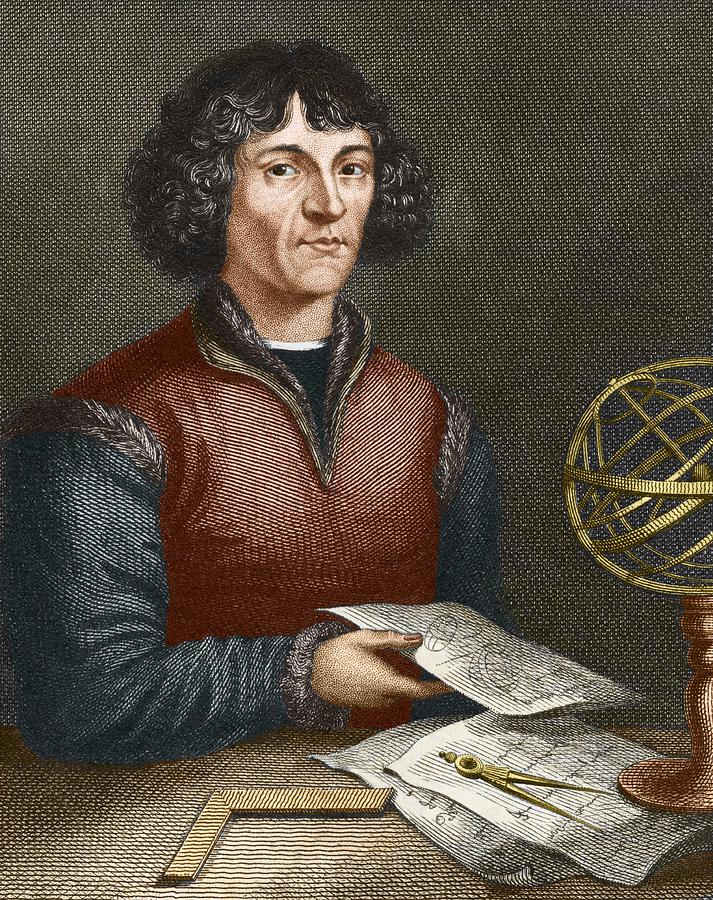

Nicolaus Copernicus, born on February 19, 1473, in Toruń, Poland, was a Renaissance polymath whose revolutionary ideas in astronomy laid the groundwork for modern science. Copernicus is best known for his heliocentric theory of the universe, which posited that the Earth and other planets revolve around the Sun. This theory fundamentally challenged the geocentric model, which had been widely accepted since the time of Ptolemy.

Copernicus was born into a well-off merchant family. After the early death of his father, his uncle, Lucas Watzenrode the Younger, took him under his wing. Watzenrode, a bishop, ensured that Copernicus received a comprehensive education. Copernicus studied at the University of Kraków, where he developed a keen interest in astronomy and mathematics. He later continued his studies at various universities in Italy, including Bologna, Padua, and Ferrara, where he immersed himself in law, medicine, and the liberal arts.

While studying in Italy, Copernicus met prominent astronomers and mathematicians who influenced his thinking. It was during this period that he began formulating his heliocentric theory. The prevailing geocentric model, endorsed by the Catholic Church, placed the Earth at the center of the universe with all celestial bodies orbiting it. However, this model struggled to explain the observed irregularities in planetary motions.

Copernicus’ heliocentric theory proposed that the Sun, not the Earth, was at the center of the universe. This radical idea simplified the explanation of retrograde motion, where planets appear to move backward in their orbits, and provided a more coherent model of the solar system. His seminal work, “De revolutionibus orbium coelestium” (“On the Revolutions of the Celestial Spheres”), was published in 1543, the year of his death. The book meticulously detailed his observations and mathematical calculations supporting the heliocentric theory.

One of the most striking aspects of Copernicus’ work was his reliance on empirical evidence and mathematical precision. Although his model still assumed circular orbits and uniform speeds, which were later corrected by Kepler’s laws of planetary motion, it marked a significant departure from the purely philosophical arguments that had dominated astronomy.

Despite its revolutionary nature, “De revolutionibus” did not immediately overturn the geocentric model. The Catholic Church, initially, did not view it as a significant threat. However, as the implications of a heliocentric universe became more apparent, the book was placed on the Church’s Index of Forbidden Books in 1616. It took the work of later scientists, such as Galileo Galilei and Johannes Kepler, to provide further empirical evidence that validated Copernicus’ ideas and gradually led to the widespread acceptance of the heliocentric model.

Copernicus’ contributions extended beyond astronomy. He was also a mathematician, physician, classical scholar, translator, governor, diplomat, and economist. His work on monetary reform was highly regarded, and his Gresham’s Law—a theory related to currency devaluation—demonstrates his diverse intellectual pursuits.

Nicolaus Copernicus’ heliocentric theory revolutionized our understanding of the cosmos. By displacing the Earth from the center of the universe, he challenged humanity’s perceived position in the grand scheme of existence. This paradigm shift not only paved the way for modern astronomy but also spurred a broader scientific revolution. It encouraged a spirit of inquiry and skepticism that is the hallmark of scientific endeavor. Copernicus’ legacy endures as a testament to the transformative power of bold ideas and meticulous scientific inquiry in advancing human knowledge.